Charge

Electricity begins with electric force.

Electric force can be explained by saying matter has a property called charge.

Written by Willy McAllister.

Contents

- Eels and amber

- Making sense of electric force

- Making sense of charge

- Benjamin Franklin

- Charles Augustin de Coulomb

- Coulomb - the unit of charge

- Electron

Where we’re headed

-

There are two types of charge. Benjamin Franklin gave us the names for charge, Plus and Minus.

-

Like charges repel each other, $+$ repels $+$, $-$ repels $-$.

-

Unlike charges attract each other, $+$ attracts $-$.

-

Charles Augustin de Coulomb worked out how the electric force behaves. He showed the electric force is proportional to the product of the two charges $(q_1, q_2)$, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. This is called Coulomb’s Law.

$F_e \propto \dfrac{q_1 \, q_2}{r^2}$

-

The smallest charged objects we know of are the electron $(-)$ and the proton $(+)$. They have the same charge, with opposite signs.

-

$1$ coulomb is defined as the total charge of $6.242 \times 10^{18}$ elementary charges.

-

The charge on an electron is $e^- = -1.602 \times 10^{-19}$ coulombs.

A good way to learn about charge is to understand its historical development. The idea of charge came about to explain the existence of electric force.

Eels and amber

For the moment, pretend you never heard of electricity. Forget you know about atoms.

5000 years ago Egyptians knew if you touched an eel it could give you a shock. Texts refer to eels as “Thunderer of the Nile.” They didn’t know what was happening, but they used to tell sick people to touch eels, and sometimes it made them feel better (other times probably not). So the very first practical application of electricity was in medicine.

2600 years ago the Greeks made jewelry out of a pretty stone called amber. Amber isn’t really a stone, it is fossilized resin from trees. Resin is a goopy substance trees make as a defense to fight off insects and cover wounds (broken branches). Sometimes this goopy resin drips from the tree, turns into a solid (fossilizes), and gets the name amber. Amber is basically a natural version of plastic.

Egyptian or Greek aristocrats lounging around wearing their fancy amber jewelry would pet their cats with it. They noticed the amber attracted feathers and hair. Today we have a word for this, the triboelectric effect. “Tribo-“ is Greek for “rub”, so it means “rubbing-electric” effect.

You get the same effect passing a plastic comb through your dry hair, or rubbing a balloon on your sweater. The comb makes your hair stand up. The balloon attracts things but repels other rubbed balloons.

The Greek word for amber is ἤ λ ε κ τ ρ ο ν.

| ἤ | λ | ε | κ | τ | ρ | ο | ν |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eta | lambda | epsilon | kappa | tau | rho | omicron | nu |

| e | l | e | k | t | r | o | n |

I bet you can guess what we use this word for.

Making sense of electric force

So we have these observations of nature: rubbing cats or balloons. We observe this invisible “amber force,” sometimes attraction, sometimes repulsion, depending on what was rubbed. So from the very beginning we could tell there were two kinds of electric force, attraction and repulsion. Even stranger, the force acts at a distance. The two objects don’t have to be touching yet we see this obvious pushing or pulling force between them. This is super weird (and super fascinating).

Is amber force is the same as magnetism?

This rubbing-cats force seems kind of like magnetism, which has two kinds and the same force at a distance property. But electric force has to come from a different place. Magnetism is a property of certain kinds of rocks called lodestones (a rock that contains iron). The electric force comes from the friction between amber and cat and has nothing to do with iron.

As you study electrical engineering or physics you learn that electricity and magnetism are closely related. When these ideas come together we merge their names and call it electromagnetism.

Gravity also has the same force at a distance feature, but there is only one kind of gravity (only attraction). So it is a very different kind of force.

The best explanation anyone has come up with (so far) to make sense of electric force is: Physical objects (matter) displaying this electric force possess a property called charge.

What is a “property of matter”?

Matter has a number of properties: mass, color, volume, squishiness. These are not little things that are inside the matter; they are aspects of the matter itself. When an object attracts or repels nearby objects we say it has the property of charge. Charge is not some little tiny piece of stuff tucked inside electrons and protons, it is a property of those particles.

Making sense of charge

Now we know why there is electric force—it’s because objects have charge.

That’s great. So uhh, what is charge?

To this day, we have no idea why this rub-the-cat electric force exists, just like we don’t know why gravity exists. It just does. We made up a story about charge to make us feel like we know what’s going on. If we embrace the idea of charge it leads us in the right direction for understanding electricity.

The whole “acting at a distance” thing has always been puzzling, but we don’t have a better explanation. When we study electrostatics, we draw lines of force leading away from charges flowing out into nothing. We play-act that these lines are real and we stick with this theory as long as it produces great results, which it does. This is a problem for physicists to ponder while electrical engineers go off and build stuff.

Benjamin Franklin

In 1752 Ben Franklin nearly killed himself while flying a kite in a lightning storm. He wanted to show that lightning was made of electricity. He could tell because the key attached to the wet kite string gave off sparks and tingled his knuckles, the same as if you shuffled your feet on the carpet and touched a doorknob.

There was great debate about the nature of electricity in Franklin’s time. Many physicists thought of it as two invisible fluids. Franklin thought of electricity as a single electric fluid. While doing rubbing experiments he theorized that rubbing caused one object to lose some invisible electric fluid while the other object gained fluid. Franklin coined the word charge and gave us the names of the two charges, positive and negative.

What’s in a name?

The names $+$ and $-$ made sense. If you let equal amounts of the two charges come together you get zero charge (neutral). So charge seems like it can be described with positive and negative numbers because of the way it combines.

But Franklin could have chosen another pair of words instead of the signs we use for numbers. Like maybe “in” and “out” or “red” and “blue”. After all, there are two kinds of magnetism. The poles of a magnet are not called $+$ and $-$, they are called North and South. In some ways I wish he had picked different names. The choice of number signs for charge causes some confusion when we pick the direction of positive current flow.

Franklin coined a number of electrical terms: battery, charge, conductor, plus, minus, condenser (another name for a capacitor).

So now we have a name for this electricity stuff. Charge!

Charles Augustin de Coulomb

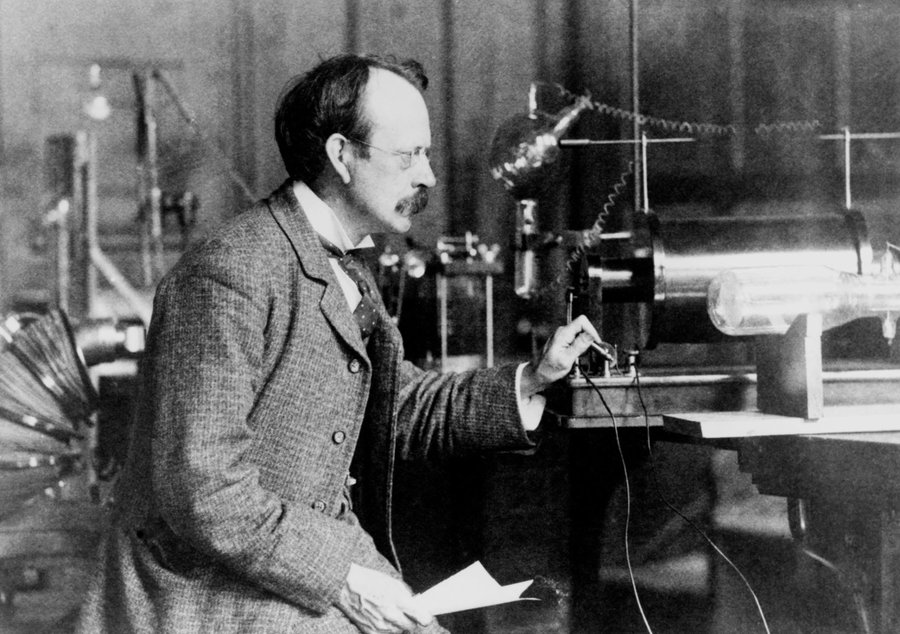

Even if we can’t explain why there is electric force (attraction and repulsion), we can describe what it does. The first person to do a good job of this was French physicist Charles Augustin de Coulomb, in 1784. This was 30 years after Franklin, but still 113 years before the discovery of the electron in 1897 (J.J. Thomson). So Coulomb (and Franklin) worked with the idea of charge without knowing about electrons or protons.

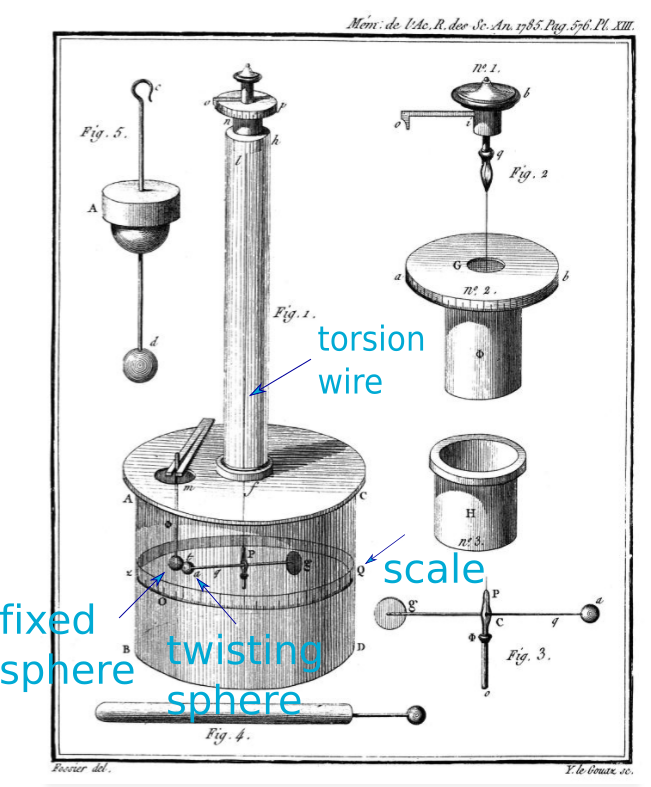

Coulomb invented a very sensitive instrument to measure electric force, the torsion balance. He put different amounts of charge on spheres (two little cannonballs) and measured the electric force between them with his sensitive torsion balance. Then he worked out an equation that gave the same result as his data.

Coulomb’s torsion balance

The torsion balance is based on twisting a fine wire. It works like a car tire hanging by a rope from a tree branch. If you sit quietly in the tire, a small nudge makes you twist back and forth. Eventually you stop twisting and come to a stand-still at some angle where the rope feels most relaxed (no twist).

(Optional) Coulomb drew this illustration of his torsion balance,

Two spheres are placed inside a chamber (Figure 1). The fixed sphere on the left (b) sits still while the twisting sphere on the right (a) hangs by a thin torsion wire and an arm (P and Figure 3). If electric force is present between the two spheres they are attracted or repelled. The sphere (a) twists toward or away from sphere (b).

The fixed sphere (b) starts out uncharged. You put a charge on the twisting sphere (a) and it swing sideways back and forth until it comes to rest at some position. The position is measured on the scale (Q) marked on the outside of the chamber.

Then you put some charge on the fixed sphere by touching the post holding it in place (m and Figure 5)—near the clamp that looks like chopsticks. This changes the electric force between the spheres and causes the twisting sphere to rotate either toward or away from the fixed sphere, depending on the sign of both charges. The electric force is opposed by the the thin wire trying to untwist itself. Wait for the twisting to stop and read the new position.

The big cylindrical chamber is sealed to prevent breezes from messing up the measurement. It is made of glass so you can see inside. The other figures are close-up views of the important bits and pieces of the main instrument.

How did Coulomb measure charge before there was a coulomb?

Coulomb did not have very good control over how much charge was applied to the spheres. One sphere had “some charge” and was attracted to the other sphere that had “some charge.” But, he did have good control of ratios of charge. He was quite smart about how he applied the charge.

For example, start with no charge on the two spheres. You can tell they are uncharged because they don’t attract or repel. Now put some charge on one sphere, let’s call it $q$. ($Q$ or $q$ are the variable names Coulomb used for charge, and we still use them today.) If you touch the charged sphere to the uncharged sphere, they will share $q$ evenly between them. You don’t know what the charge is precisely, but you know they are both charged the same, both with a charge of $q/2$.

Can you think of a way to charge a sphere with $q/4$?

Coulomb demonstrated the electric force is proportional to the amount of charge on each object and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them $(1/r^2)$. We call it Coulomb’s Law.

$F \propto \dfrac{q_1\,q_2}{r^2}$

The $\propto$ symbol means “proportional to”. We will replace it with an $=$ sign by including a constant of proportionality in the equation in the article on electric force.

Check out this marvelous 1959 educational video with Professor Eric Rogers from Princeton University demonstrating electric force. See how Professor Rogers transfers charge from his “charging arrangement” machine to one balloon and then shares that charge with another balloon.

Coulomb - the unit of charge

The unit of charge is named the coulomb, in honor of guess who.

$1$ coulomb is defined in terms of the elementary charge on a proton,

$1 \,\text{coulomb} = 6.241509074 \times 10^{18} \,\text{elementary charges}$

Think of a coulomb as a bucket of charge, like a bucket of water. If you put $6.241509074 \times 10^{18}$ protons in a bucket then the bucket contains $+1$ coulomb of charge. If the bucket had this many electrons the charge would be $-1$ coulomb.

If we take the reciprocal we derive the charge on an electron in terms of coulombs.

$e^- = -\dfrac{1}{6.242 \times 10^{18}} = -1.603 \times 10^{-19}\,\text{coulomb}$

You can scoop smaller amounts of charge out of the bucket to get microcoulomb $(\mu\text C)$ or nanocoulomb $(\text{nC})$ of charge.

Franklin thought of charge as a continuous fluid. That’s how we are thinking about it when we measure charge in coulombs.

It’s amazing, but the classical fields of electrostatics (what we are studying here) and electrodynamics developed in the late 1800’s did not predict or depend on knowing about the existence of the electron.

Electron

The electron was discovered in 1892 (J.J. Thomson). We now know the smallest charged objects are two sub-atomic particles, the electron $(-)$ and the proton $(+)$. The amounts of charge on the electron and proton are identical, with opposite signs. The mass of electron is $1000\times$ less than a proton, but the charge of the two particles is identical. We don’t know why, we just know Nature made it that way.

The electron gets the $-$ sign and the proton the $+$ sign because of the way Franklin stated his “one fluid” theory of electricity so long ago. The material he thought was lacking electric fluid had picked up extra electrons from the other material used to rub it. There was no way to know this at the time. The important point to remember is the signs/names we use for charge are arbitrary. There is nothing naturally “negative” about the electron’s charge; its only true property is that it is unlike the charge of the proton. It’s just a name.

The variable we use for the charge of an electron is $-e$ or $e^-$. The charge of a proton can be written as $+e$ or $e^+$.

J. J. Thomson in his laboratory at Cambridge University, England.

J. J. Thomson in his laboratory at Cambridge University, England.

Summary

The concept of charge explains why there is electric force.

There are two types of charge. Like charges repel, and unlike charges attract.

Franklin gave us the names of charge, positive and negative.

Coulomb worked out the equation that describes the effect of charge.

The unit of charge is the coulomb, defined as a number of elementary charges.

Questions

typo error under “Electron”, paragraph 2, sentence 2: “though” should be “thought”.

I actually had A doubt that I wanted to clear .is there any way I can contact you??

My email address is at the bottom of the page.

thanks a lot .. I actually reffered to a lot of sites/books for the basics but you guys made it so simple ..again thanks a lottt

I love hearing that. Good luck in your studies.

Nice intro, thanks!

Omar - Thanks for dropping in. I hope you enjoy Spinning Numbers.