Decibel

The decibel $(\text{dB})$ unit measures the ratio between two quantities. That means the decibel is a relative measurement. Its main application is to measure the ratio of power.

The definition of a decibel can be modified to measure the ratio of voltages or currents.

The decibel uses base-$10$ logarithms. To brush up on your logarithms, pay Sal a visit.

Written by Willy McAllister.

Contents

- Back story

- Definition

- Comparing voltages using decibels

- Review the assumption about resistance

- Where do you see dB units?

- Relative to watt?

- dB calculators

- dB charts

Where we’re headed

Gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$ for a power ratio.

Gain in $\text{dB} = 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$ for a voltage ratio.

We use the second definition for anything proportional to the square root of power—voltage, current, sound intensity, etc.

A negative $\text{dB}$ value corresponds to gain less than $1$.

Back story

To understand the decibel it helps to know where it came from. Why is there a $\log$? why is there a $10$? If you want, hop over this part and go to the definition section.

The decibel was invented by engineers at the Bell Telephone Co. in the 1920’s (now AT&T). Bell engineers wanted to express how much power was gained in an amplifier or how much power was lost driving a phone signal down a long copper transmission line.

Low-power phone signal $p_0$ is amplified by $A_1$ to higher power $p_1$ and sent down transmission line $T_1$. Over distance the signal power diminishes down to $p_2$. It has to be amplified again by $A_2$ restoring it to higher power $p_3$ to continue the trip. This process happens over and over again for a long-distance phone call.

Just making up numbers, suppose the incoming signal is $p_0 = 1 \,\text{mW}$. We want to drive the land line with a $p_1 = 1\,\text W$ signal. Amplifier $A_1$ provides the necessary gain. The signal travels down the long transmission line and loses almost all of its energy into the resistance of the line. Miles or kilometers away the signal has attenuated down to $p_2 = 0.01\,\text{mW}$ (attenuate means loss). Amplifier $A_2$ receives the signal and boosts it back up again to $p_3$.

We want to measure gain and attenuation with numbers. The first thing we might try is a simple ratio. The power before and after the first amplifier is,

$A_1 = \dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = \dfrac{1}{0.001} = 1000$

The term on the bottom, $p_0$, is the reference value. We are comparing the term on top, $p_1$, to the reference value.

The power attenuation down the line is,

$T_1 = \dfrac{p_2}{p_1} = \dfrac{0.00001}{1} = 1/10{,}000$

This works fine. However, the numbers involved can be very big and very small. Writing big and small numbers is error-prone if you miscount the zeros.

A good way to compress a wide number range is to take its logarithm. (This is the convenient feature of scientific notation with the exponent of $10$.) Let’s try that with power ratios. Bell engineers defined a new unit called the $\text{bel}$ named after their company founder, Alexander Graham Bell. A bel is the logarithm of the ratio, abbreviated $\text B$,

power gain in $\text{bel} = \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

We can express the amplifier power gain in bels,

$A_1 = \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = \log_{10}\dfrac{1}{0.001} = \log_{10} 1000 = +3\,\text{bel} = 3\,\text B$

The attenuation of the transmission line in bels is,

$T_1 = \log_{10}\dfrac{p_2}{p_1} = \log_{10}\dfrac{0.00001}{1} = \log_{10}1/10{,}000 = -4\,\text B$

Attenuation has a negative $\text{bel}$ value after taking the logarithm. Ratios less than $1$ come out with a negative sign in bels.

If the terms in the ratio happen to be the same then you get zero bel,

$\log_{10}\dfrac{p}{p} = \log_{10} 1 = 0\,\text B$

So far so good. We have a compact notation. But there’s a small irritation when the ratio of power is small. For aesthetic purposes, we would like our units to be greater than $1$ most of the time. If you have a power ratio of $2:1$ the gain in bels is,

$\log_{10} \dfrac{2}{1} = \log_{10} 2 = 0.301\,\text{bel}$

This means the bel unit is inconveniently large. Bell engineers said, “We want the number to be a little bigger. What the heck. We’ll divide the bel by $10$ and call it a deci-bel and multiply the answer by ten so it means the same thing.” $1\,\text{bel} = 10\,\text{decibel}$. As long as you are making up a unit, you might as well make it a unit you want.

deci-

The prefix deci- comes from the Latin word decimus for one tenth. It is also the name of our number system, the decimal system. Decibel means literally one-tenth bel.

Definition

This practical chain of reasoning lead Bell engineers to define the decibel we use today, abbreviated $\text{dB}$,

$\boxed{\text{Gain in }\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}}$

Notice the decibel is a dimensionless quantity. It’s not $\text{dB}$ of watts, it’s just $\text{dB}$.

Example 1

Express a power ratio of $2:1$ in decibels.

From the definition of decibel,

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10} \dfrac{2}{1} = 10 \log_{10} 2 = 3.01\,\text{dB}$.

Use your calculator to compute the log or tell Google: 10*log10(2)

or use the power ratio to dB calculator.

Now flip the power ratio to $1:2$ and figure out what that means in decibels,

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10} \dfrac{1}{2} = 10 \log_{10} 0.5 = -3.01\,\text{dB}$

By the way, these are good $\text{dB}$ values to memorize,

Twice the power is $+3\,\text{dB}$. Half the power is $-3\,\text{dB}$.

Example 2

Let $p_1 = 2\,\text W$ and the reference value $p_0 = 0.02\,\text W$.

What is the power ratio in decibels?

Hint: Use your calculator to compute the log, or enter 10*log10(2/0.02) into Google.

show answer

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{2}{0.02}$

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10} 100$

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \cdot 2$

gain in $\text{dB} = 20\,\text{dB}$

Extra credit: What is the decibel measure if you reverse $p_0$ and $p_1$?

More extra credit: What is the decibel measure if $p_0 = p_1$?

Example 3

Now we go the other way. I tell you the power gain in decibels is $15\,\text{dB}$,

What is the ratio of the two powers?

Hint: Work the logarithm backwards to find the ratio.

show answer

We know the $\text{dB}$ and we’re asked to find $\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$.

gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

$15\,\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

$15\,\text{dB}/10 = \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

Raise each side up to be a power of $10$,

$10^{15\,\text{dB}/10} = 10^{\log_{10}p_1/p_0}$

On the right side, the “$10$-to-the” and the log function cancel each other, leaving behind the argument of the log,

$10^{1.5} = \dfrac{p_1}{p_0}$

$\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 31.62$

A gain of $15\,\text{dB}$ represents a power ratio of $31.62:1$.

In general, to go from $\text{dB}$ to power ratio,

$\boxed{\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 10^{\text{dB}/10}}$

Comparing voltages using decibels

There’s one more finesse. What happens if we try to measure voltage gain in dB? If we define this carefully, we might even be able to compare voltage $\text{dB}$’s with power $\text{dB}$’s directly.

The first thing you might try is the same definition of decibel,

gain in $\text{dB} \stackrel{?}{=} 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

This definition has the same features as power decibels, with a nice compression and reasonable range. But, if you compute $\text{dB}$’s using the power and voltage of the same signal, they don’t match.

show me the problem

Set up a $50\,\Omega$ resistor with $1\,\text V$ across it.

The power in the resistor is $p = v^2/\text R = 1^2/50 = 0.020 = 20\,\text{mW}$

Then change the voltage to $2\,\text V$.

The power goes up to $p = v^2/\text R = 2^2/50 = 0.080 = 80\,\text{mW}$

Compute the gain in voltage and power with the proposed definition of voltage $\text{dB}$.

voltage gain in $\text{dB} \stackrel{?}{=} 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{2\,\text V}{1\,\text V} = 3\,\text{dB}$

power gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{80\,\text{mW}}{20\,\text{mW}} = 6\,\text{dB}$

The two calculations are different by a factor of two. We can’t directly compare voltage decibels to power decibels unless we use a conversion factor. With this definition of voltage $\text{dB}$’s we would have to remember “kinds” of $\text{dB}$, like voltage decibels and power decibels. That’s lame. We can do better.

What do we have to do to get the same decibel value for power and voltage? Voltage and power have a specific relationship. The power in a signal is $p = i\,v$. If the voltage appears across a resistor we use Ohm’s Law to express power in terms of voltage,

$p = i\,v = \dfrac{v}{\text R}\cdot v = \dfrac{v^2}{\text R}$

Power $p$ is proportional to voltage squared $v^2$. Power and voltage have a square relationship. If you say it backwards, they have a square-root relationship.

Write the definition of decibel using $v^2/\text{R}$,

$10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1^2/\text R_1}{v_0^2/\text R_0}$

Let’s assume the resistors have the same value. That makes them cancel out. (This is an important assumption. We’ll talk about this again.)

$10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1^2}{v_0^2} = 10 \log_{10} \left (\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}\right )^2$

It is possible to simplify the $v^2$ term using the power property of logarithms. The power property says if you have an exponent, $y$, inside a logarithm you can move it out in front of the log,

$\log_{10} x^y = y \log_{10} x\qquad$ power property of logarithms

We do this to the $v^2$ fraction,

$10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1^2}{v_0^2} = 2 \cdot 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

The leading $10$ turns into a $20$ and gives us the definition of a decibel when taking the ratio of voltages (or any other quantity proportional to the square root of power),

$\boxed{\text{Gain in } \text{dB} = 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}}$

It may seem goofy to have a second definition for the decibel, but we need it to get a consistent meaning for $\text{dB}$.

Example 4

Now we redo the calculation from up above in the “show me the problem” hint. This time using the proper definition of decibel for voltage ratios.

Set up a $50\,\Omega$ resistor with $1\,\text V$ across it.

The power in the resistor is $p = v^2/\text R = 1^2/50 = 0.020 = 20\,\text{mW}$

Then change the voltage to $2\,\text V$.

The power goes up to $p = v^2/\text R = 2^2/50 = 0.080 = 80\,\text{mW}$

Compute the gain in voltage and power with the revised definition of $\text{dB}$ for voltage.

voltage gain in $\text{dB} \stackrel{!}{=} 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0} = 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{2\,\text V}{1\,\text V} = 6\,\text{dB}$

power gain in $\text{dB} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{p_1}{p_0} = 10 \log_{10}\dfrac{80\,\text{mW}}{20\,\text{mW}} = 6\,\text{dB}$

The two calculations give the same answer when we use the proper definition of decibel for voltage ratios. We did better.

Example 5

Express a voltage ratio of $2:1$ in decibels.

From the definition of decibel,

gain in $\text{dB} = 20 \log_{10} \dfrac{2}{1} = 20 \log_{10} 2 = 6.02\,\text{dB}$.

Use your calculator to compute the log or tell Google: 20*log10(2)

or use the voltage ratio to dB calculator.

Example 6

Now we go the other way with voltage ratios. I tell you the gain in decibels is $3\,\text{dB}$,

What is the ratio of the two voltages?

Hint: This is the same derivation we did in Example 3, but with the definition of decibels for voltage ratios.

show answer

We know the $\text{dB}$ and we’re asked to find $\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$.

gain in $\text{dB} = 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

$3\,\text{dB} = 20 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

$3\,\text{dB}/20 = \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

Raise each side up to be a power of $10$,

$10^{3\,\text{dB}/20} = 10^{\log_{10}v_1/v_0}$

On the right side, the “$10$-to-the” and the log cancel each other, leaving behind the argument of the log,

$10^{3/20} = \dfrac{v_1}{v_0}$

$\dfrac{v_1}{v_0} = 1.4125$

A gain of $3\,\text{dB}$ represents a voltage ratio of $1.41:1$.

Compare this voltage ratio to the the power ratio we worked out in Example 1.

In general, to go from $\text{dB}$ to voltage ratio,

$\boxed{\dfrac{v_1}{v_0} = 10^{\text{dB}/20}}$

Example 7

The gain of an amplifier is $100\,\text{dB}$.

What is the ratio of the output voltage to input voltage?

show answer

$\dfrac{v_{out}}{v_{in}} = 10^{\text{dB}/20}$

$\dfrac{v_{out}}{v_{in}} = 10^{100/20}$

$\dfrac{v_{out}}{v_{in}} = 10^5$

$\dfrac{v_{out}}{v_{in}} = 100{,}000$

Modern opamp chips achieve this level of gain.

Review the assumption about resistance

When we defined decibels for voltage ratios we assumed the two resistors in

$10 \log_{10}\dfrac{v_1^2/\text R_1}{v_0^2/\text R_0}$ had the same value. Let’s talk about when that’s a good assumption.

This assumption is easy to meet if the top and bottom voltages are the same point in the circuit. There’s just one resistor to worry about. For example, if you look at the voltage output of a filter and you want to compare low-frequency response to high-frequency response, they are measured at the same physical node, so $\text R$ is the same.

If the voltages are not measured at the same point then the assumption works if the two points have the same resistance. An example is an amplifier with an input resistance of $50\,\Omega$ driving a load of $50\,\Omega$. You get an accurate $\text{dB}$ reading for the gain of the amplifier when two different $\text R$’s have the same value.

The assumption is not met if the resistance at two points is different. In spite of this, it is quite common for engineers to present voltage ratios in $\text{dB}$ even if the resistors are not the same. The number you get is an accurate reflection of the voltage gain, but you have to be cautious if comparing it to other $\text{dB}$ derived from power. They are not the same animal.

Where do you see dB units?

$\text{dB}$ units are commonly used to measure

- gain of amplifiers

- attenuation of filters

- signal to noise ratio (SNR)

Amplifier: An amplifier can be characterized in terms of $\text{dB}$ of gain. If the voltage gain of an amplifier is $v_o/v_i = 100$, that’s equivalent to a gain of $40\,\text{dB}$. (Try it in the voltage ratio to dB calculator.)

Filter: $\text{dB}$ is used to characterize analog and digital filters. When you simulate a filter the magnitude scale is almost always presented in $\text{dB}$. SPICE and Circuit Sandbox use $\text{dB}$ on the vertical scale of AC magnitude plots. Open this circuit model to see an example. Run an AC simulation. On the magnitude plot hold the mouse near $4\,\text{kHz}$ on the frequency scale. The filter response is $-35.965\,\text{dB}$ at that frequency. Use the dB to voltage ratio calculator to find out how small the output is relative to the input at $4\,\text{kHz}$.

SNR: Electronic systems always have background noise. Noise can be a faint hiss caused by electrons striking atoms, or it can be caused outside interference from other electrical sources. It is common to compare the power of the intended signal to the power of the noise, expressing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in decibels. A high-en stereo system with undetectable background noise has high SNR. A really bad scratchy phone connection you can hardly understand has low SNR.

Relative to watt?

If you’ve been following along you know the decibel is a relative measure. It always involves a ratio of two numbers. What happens if you come across a $\text{dB}$ reading for one number? The text will make it sound as if there is an absolute decibel scale. But there is not. It means one of the numbers is missing, and it is always the reference value that’s unstated.

When this happens there is a reference value hiding somewhere in the vicinity. Sometimes the reference value is supposed to be “understood” because of the context. If you are not an insider in a specific technical field you have to look around the article or ask someone or see if Google can tell you.

Often the reference is tucked into the decibel unit with an extra letter added to $\text{dB}$,

$\text{dBm}$ — The “m” suffix means the reference value is $1\,\text{mW}$.

$\text{dBV}$ — The “V” suffix means the reference value is $1\,\text{V}$.

There is no consistency to this, and there’s a whole alphabet soup of suffixes. A lot of them are listed on the Wikipedia page for the decibel. It’s unfortunate, but using decibels sometimes forces you do extra work to find the reference.

dB calculators

Here are some simple calculators for the four boxed decibel equations.

Power ratio to dB

$p_1$

$p_0$

$= 10\,\log{p_1 / p_0}$

$\text{dB}$

Voltage ratio to dB

$v_1$

$v_0$

$= 20\,\log{v_1 / v_0}$

$\text{dB}$

db to power ratio

$\text{dB}$

$= 10^{\text{dB}/10}$

$p_1/p_0$

dB to voltage ratio

$\text{dB}$

$= 10^{\text{dB}/20}$

$v_1/v_0$

dB charts

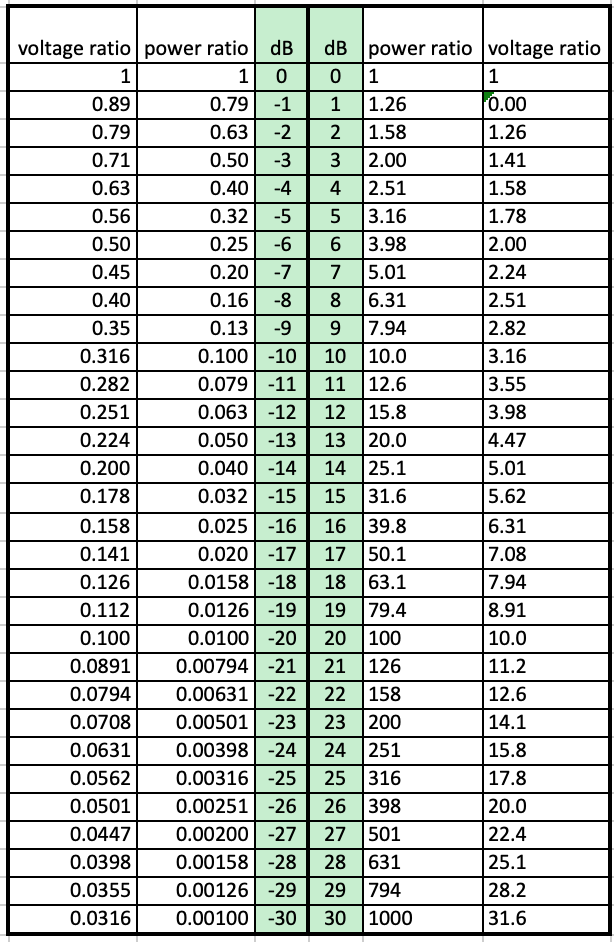

My intuition for the decibel scale isn’t so good. I have a better feel for power and voltage ratios. When I’m working with decibels I print out a dB chart and pin it up near my work area. You can generate your own dB chart in Excel. Here are Excel formulas for converting to and from dB.

=10*LOG10(Z3) convert power ratio in cell Z3 to dB

=POWER(10,(B3/10)) convert dB in cell B3 to power ratio

=20*LOG10(Y3) convert voltage ratio in cell Y3 to dB

=POWER(10,(B3/20)) convert dB in cell B3 to voltage ratio

Here’s a sample of my Excel spreadsheet that uses these formulas.

Summary

There are two definitions of the decibel, depending on if you are comparing power terms or root-power terms (voltage or current).

Gain in $\text{dB} = 10\,\log{\dfrac{p_1}{p_0}} \,\text{dB}$ for comparing power.

Gain in $\text{dB} = 20\,\log{\dfrac{v_1}{v_0}} \,\text{dB}$ for comparing root-power terms.

By having two definitions for $\text{dB}$ we directly compare power ratios and voltage ratios when they are expressed in decibels.

To use the decibel you need to understand a few things,

- The decibel a logarithmic measurement. In particular $\log_{10}$.

- The decibel is a ratio. A ratio has a top and a bottom term. You have to know both.

- The terms in the ratio can be either,

- two power terms

- two root-power terms (like two voltages or two currents)

- The two terms have to have the same units—you don’t mix units.

- The decibel is dimensionless.