Inductor - how it works

STILL UNDER CONSTRUCTION

When this article is ready to publish, add this line back to Ideal or Real World elements:

Refer to Inductor - how it works for an informal description of how an inductor does its thing.

When you make an inductor the goal is to create a component that behaves like the ideal inductor equation,

$v = \text L \,\dfrac{di}{dt}$

I don’t tell you why we want this equation. We will talk about that another time. For now, we want to build a physical object that creates the inductor $i$-$v$ (current-voltage) equation.

The theory of how inductors actually work is pretty complicated. To learn more about inductors and magnetic fields, see the magnetic fields section of Khan Academy Physics.

Written by Willy McAllister.

Contents

- First, a little magnetism

- Inductor $i$-$v$ equation

- Increasing inductance

- Inductor slang

- Flywheel analogy

- A few more remarks on electromagnetism

First, a little magnetism

Any wire carrying a current generates a magnetic field in the surrounding region. This important fact was discovered by Danish scientist Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820. Up to that time, everyone thought electricity and magnetism were separate things. Ørsted showed they were related, and we call the merged concept electromagnetism.

The red lines in these images represent the magnetic field. Here’s a single straight wire carrying a current, $i$. Whenever there is a current, there are magnetic field lines flowing in circles in the space around the wire.

How do we know the magnetic field is there?

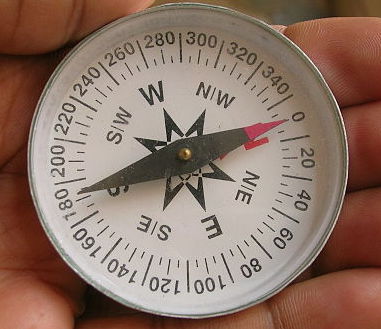

How can you tell if there is a magnetic field near the wire?

By using a magnetic field sensor, of course.

You already know what that is, it’s called a compass.

If there is no nearby magnetic field, the needle of the compass lines up with the magnetic field of the Earth, and points to magnetic north. If you create a magnetic field, the compass needle swings around and lines up with the new field. The magnetic field from the wire is stronger than the earth’s field, so it overpowers it and tips the compass needle.

Using a compass as a magnetic field sensor is an example of how we create “eyes” to “see” the invisible. Electricity and magnetism are invisible, so we build different kinds of “eyes” all the time. It is an essential skill. This is one reason people think EE’s are wizards.

Magnetic lines and the Right Hand Rule

You may notice that both current and the magnetic lines have arrowheads. The direction of these arrows is not arbitrary; it is a property of nature. If you know one of the arrows, you can figure out the other by using the Right Hand Rule.

Using your RIGHT hand, wrap your fingers around the wire with your thumb pointing in the direction of current (conventional current flow, not electron flow). The magnetic field line arrows will be flowing out of your fingertips.

Pro tip: If you are right-handed, put your pencil down when you use the rule. The most common error is using your left hand to do the Right Hand Rule, which gives you the wrong answer. If your left hand needs something to do, use it as the wire.

If you ever peek into a classroom during a test on Electricity and Magnetism, you will see all the students using this rule. It looks pretty funny.

So now we have something called an inductor. It’s just a straight wire, but it has a magnetic field surrounding it caused by the current. Let’s figure out why it follows the inductor $i$-$v$ equation.

Inductor $i$-$v$ equation

So where does the inductor $i$-$v$ equation come from? Here are some observations about Ørsted’s experiment, plus some new information.

We start from the observation that a current (moving charge) creates a nearby magnetic field.

-

A changing current creates a changing magnetic field.

-

A changing magnetic field creates an electric field in the wire.

(This was a discovery by Michael Faraday and Joseph Henry.) -

An electric field in the wire is the same thing as saying there’s a voltage.

-

Voltage causes charge to move in the wire, so you get a current.

Do you see the circular argument? Changing current makes a changing magnetic field. Changing magnetic field makes voltage, and voltage makes current.

This seems terribly complicated.

If this seems really complicated, it seems that way to me, too.

Electromagnetism is complicated. There are a couple of reasons. Two things contribute to making electromagnetism hard to figure out,

1) One complication is that you get voltage only if the magnetic field is changing. If the magnetic field is constant (not changing), you get no voltage, and no current. So if you just hold a magnet near a wire, nothing happens. This may seem strange, but it's what nature gives us.

2) The other complication is how magnetism and electricity interact in three dimensional space. Recall the first image in this article, with the wire and magnetic field. The plane of the magnetic lines surrounding the wire is perpendicular to the wire. This means all your math in three dimensions and you have to learn things like the Right Hand Rule and vector cross products. It's hard to hold all this in your head. Ørsted actually needed some luck to position a moving magnet at just the right angle before he figured out what was going on.

This seems terribly complicated.

If this seems really complicated, it seems that way to me, too.

Electromagnetism is complicated. There are a couple of reasons,

1) One complication is that you get voltage only if the magnetic field is changing. If the magnetic field is constant (not changing), you get no voltage, and no current. So if you just hold a magnet near a wire, nothing happens. This may seem strange, but it’s what nature gives us.

2) The other complication is how magnetism and electricity interact in three dimensional space. Recall the first image in this article, with the wire and magnetic field. The plane of the magnetic lines surrounding the wire is perpendicular to the wire. This means all your math is in three dimensions. You have to learn things like the Right Hand Rule and vector cross products. Ørsted actually needed some luck to position a moving magnet at just the right angle before he figured out what was going on.

Now we can explain the key trick performed by an inductor:

A changing current creates a changing magnetic field, which in turn creates a voltage. We write this mathematically with an equation you may have seen before:

$v = \text L \dfrac{di}{dt}$

The changing current is represented by $di/dt$ on the right side, along with a constant of proportionality, known as the inductance, $\text L$. And the voltage created by the changing current appears on the left side.

For a short straight wire, the value of $\text L$ is really small. It doesn’t make a very useful inductor for designing everyday circuits. However, if you are designing a very fast circuit (up in the $\text{GHz}$), where the current is changing very rapidly, (very high $di/dt$), then even the small $\text L$ of a short wire can make a difference in how the circuit works.

What does the $d$ mean?

The $d$ in ${di}/{dt}$ is notation from calculus, it means differential. You can think of $d$ as meaning "a tiny change in ..."

For example, the expression $dt$ means *a tiny change in time*. When you see $d$ in a ratio, like $di/dt$, it means, "a tiny change in $i$ (current) for each tiny change in $t$ (time)." An expression like $di/dt$ is called a derivative, and it is what you study in Differential Calculus.

Increasing inductance

The next step in building a useful inductor is to wrap the wire into a coil shape. Now we have much more wire in a small space, and get many more magnetic lines. The coil shape causes the magnetic field to become concentrated on the inside of the coil. This is how we get large values of inductance $\text L$. Adding more turns to the coil crams more magnetic lines into the core, and $\text L$ gets bigger.

Each individual little section of wire still has the same field lines as in the straight wire example. In the center of the coil, all the field lines from all the neighboring loops point in the same direction.

See if you can use the Right Hand Rule to confirm that the magnetic field line arrows in the coil images are correct.

The symbol for an inductor looks like this,

It looks like a wire wrapped around in a coil, since that is the usual way to make an inductor.

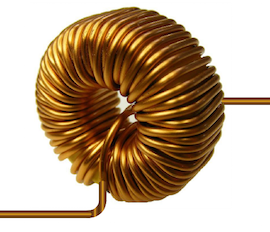

Increasing inductance even more

You can get even higher inductance (higher $\text{L}$) by putting magnetic material inside the coil to intensify the magnetic field even more. This toroidal inductor (toroid means donut-shaped) is wound around a core of iron/ceramic material called ferrite. (You can’t see the ferrite core, it is covered by the copper wire.)

The ferrite core concentrates and intensifies the magnetic field more than just an air core, which increases the value of inductance, $\text{L}$.

Inductor slang

You will sometimes hear people say an inductor “wants” to keep current flowing. Little coils of wire can’t actually “want” anything, but this is a useful idea. It comes from the back-and-forth dance between current and magnetic field. Once a magnetic field builds up around an inductor, it keeps pushing current in the wire. The current and magnetic field have a reinforcing effect on each other, they induce each other. This is where the inductor gets its name.

Flywheel analogy

A flywheel is a wheel with a heavy rim.

Inductance in an electrical system is analogous to mass in a mechanical system. Energy is stored in the magnetic field of the inductor in the same way kinetic energy is stored in a moving mass.

You can think of an inductor like a rotating flywheel. Once it starts spinning, you can’t instantly stop a spinning flywheel. There’s a lot of energy stored in the wheel. If you spin a bicycle wheel really fast and then grab it with your hand, the wheel takes a little while to stop and a lot of energy is delivered to your hand. It seems like the wheel “wants” to keep going. Likewise, the current in an inductor keeps going and does not change in an instant.

A few more remarks on electromagnetism

Here are a few more interesting points about electromagnetism.

-

The voltage generated by a changing magnetic field has a formal name, it is called an electromotive force, or emf. This is why you often see the variable name $e$ or $\text E$ used to represent voltage.

-

You know a voltage is created from the chemical reactions inside a battery. A changing magnetic field also creates a voltage! Oh my goodness! Now you know two ways to create voltage.

-

There are two ways you can create a changing magnetic field. One way we talked about here with a changing current. The other way to generate a changing magnetic field is to actually move a magnet. This is what’s going on inside a generator at a hydroelectric dam. The falling water spins a shaft with a magnet attached. Coils of copper wire surrounding the magnet have an induced voltage that is sent to our homes to make popcorn and heat soldering irons.

Questions

“A changing current creates a changing magnetic field, which creates a constant voltage. We write this mathematically with an equation that you may have seen before: v = L (di/dt)”

You have assumed here that di/dt is constant for the Orsted experiment isn’t it?

If we have for instance i = sin(wt) the resultant voltage is another sinusoidal. Can we found circuits with current expressed by oddest mathematical functions and real utility?

Thank you!

You are correct. If the magnetic field is changing at a constant rate, you get a constant voltage. I will revise the article to just say ‘a changing magnetic field creates a voltage’.

If you apply a sine current or voltage into a system, typically every other current and voltage is some sort of sine function as well. The different signals all have different amplitude and phase delay (timing delay), but they all look like sinusoids. This is what is covered in the AC Analysis section.

If you wonder about other “odd” mathematical functions with utility, the first one I think of is the step function, just a single abrupt change from 0 volts to 1 volt. The square wave is also very useful, because it appears in every digital circuit (repeating sharp transitions from 0 to 1 to 0 to 1 , etc). The whole field of “Signals and systems” explores these types of signals. Engineers are really good at sine waves and there is a lot of beautiful theory (Fourier analysis) that tells you what a system will do with “oddball” inputs if you already know how it responds to sine waves.