RMS

We want to compare the power of an AC wave form to the power of a DC waveform (a steady level). This is done with a special kind of unit referred to as RMS.

RMS is short for root mean square, which is short for “the square root of the average (mean) of some quantity squared”. (Whew! We’ll stick with the name RMS.)

Usually RMS is used for sine waves, but the idea works for any repetitive wave form.

Written by Willy McAllister.

Contents

- Instantaneous power

- Average DC power

- Average AC power

- Match AC power to DC power

- RMS voltage

- Concept check

Where we’re headed

The RMS voltage of a sine wave is the peak value $\text V_{peak}$ divided by the square root of $2$,

$\text V_{\text{RMS}} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}}{\sqrt 2}$

If you apply sine wave voltage with this RMS value to a resistor it will heat the resistor just as much as a DC voltage with the same value. That is, a $10\,\text V_\text{RMS}$ sine wave heats a resistor the same as $10\,\text V_\text{DC}$. In this article we derive where the $\sqrt 2$ comes from.

This is a story of power and warmth.

Let’s say we have a DC voltage source driving direct current through a resistor and an AC voltage source driving alternating current through the same resistor.

Both resistors dissipate power so they both get warm. The question we want to explore is,

What AC voltage heats the resistor the same the DC voltage?

Instantaneous power

If we know the voltage across the resistor we can work out the current using Ohm’s Law. We can write the power at any particular moment three different ways,

$p = i\,v\quad$ or $\quad p = \left (\dfrac{v}{\text R}\right )\,v = \dfrac{v^2}{\text R}\quad$ or $\quad p = i\,(i\text R) = i^2\,\text R$

We call this the instantaneous power. This is true for both DC and AC as long as we think about a single moment in time.

Notice the $v^2$ or $i^2$ terms mean power is always positive, even if voltage or current is negative. It doesn’t matter which way current flows—the resistor gets warm.

This discussion is in terms of RMS voltage. The RMS concept applies to current as well.

Average DC power

For the DC circuit the voltage is constant. Therefore the power is the same for all moments in time,

$p = \dfrac{\text V^2_{\text{DC}}}{\text R}$

Average DC power is the same as instantaneous DC power.

Average AC power

For the AC circuit the voltage and current are changing all the time. Different amounts of power are delivered to the resistor at different points in the sine. That doesn’t help us answer the question about how much the resistor heats up. What does help us is to consider the average amount of power delivered to the resistor over an entire cycle of the sine wave.

When you heat a resistor with AC voltage the physical object warms up. The movement of heat is a relatively slow process. The physical bulk of the resistor smooths out the temperature variations. If you touch the resistor you feel a relatively constant temperature. The temperature does not go up and down at the frequency $\omega$. (We assume $\omega$ is at least many times per second, not really slow like once per minute or once per hour.)

The slow movement of heat through solid material justifies thinking about average power over a cycle. (We didn’t need this justification for DC power because everything is the same from moment to moment.)

Intuition

Let’s figure out the average power caused by an AC voltage.

Let $\text V_\text P = 2\,\text V$ and $\text R = 1.33\,\text k\Omega$. The radian frequency $\omega$ can be anything.

The voltage and current look like this,

In a resistor voltage (orange) and current (blue) go up and down together. If voltage is a sine, then current is also a sine. The vertical scale is $1\,\text V$ and $1\,\text{mA}$ per division. The time scale is arbitrary.

Sketch what you think the power looks like.

Copy the $i$-$v$ plot to paper and sketch in your estimate of the power waveform.

Hints: Pick one of the three forms of the power equation. Work out the power at the highest and lowest points of the voltage sine. Then work out the power where the voltage crosses zero. Then sketch the power between the points you know.

show answer

Work out some power points and graph them,

When $v = \pm \text V_{peak}$ the power is $p = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}$.

When $v = 0$ (zero-crossings) the power is $p = 0$.

Plot these four points for each cycle of $v$. Then sketch what happens between points.

It is also possible to work out the algebra. In general,

$p = \dfrac{v^2}{\text R} = \dfrac{(\text V_{peak}\sin{\omega t})^2}{\text R} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\sin^2{\omega t}$

With the values from our example circuit,

$p = \dfrac{2^2}{1333}\,\sin^2{\omega t} = 0.003\,\sin^2{\omega t} = 3\,\sin^2{\omega t}\,\text{mW}$

Voltage, current, and power (black). The vertical power scale is $1\,\text{mW}$ per division.

Power is highest at the peaks of the voltage and current sine. Power is lowest when they are near zero. In between those points the power varies between its highest point and zero. Power is proportional to voltage or current squared—the high parts are strongly reinforced—most of the power is delivered during the peaks.

You sketched a $\sin^2$ function. It looks kind of sine-ish, with a frequency twice the voltage and current waveforms. Do you think power actually is a sinusoid?

half-angle identity

Towards the end of your Trigonometry class you most likely came across the half-angle identities for sine, cosine, and tangent. We use one of them to simplify $\sin^2$,

$\sin^2 {\omega t} = \dfrac{1}{2}(1 - \cos{2\omega t})$

It is called half-angle because the angle inside $\sin^2$ on the left, $\omega t$, is half the angle of the $\cos$ term on the right, $2\omega t$.

This identity lets us rewrite power,

$p = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\sin^2{\omega t} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\dfrac{1}{2}(1 - \cos{2\omega t})$

To answer the question: Is power (a function of $\sin^2$) a sinusoid? The answer is yes. The sinusoid happens to be a cosine. $\sin^2$ is a true sinusoid, not something that just looks similar.

You shouldn’t bother to memorize the half-angle identity or its proof. If you are curious about where it comes from check what Sal has to say about in this half-angle identity video. The part we use starts at 8:20 minutes.

$\sin^2$

I like to write the half angle identity this way. It emphasizes the DC shift of $\dfrac{1}{2}$,

$\sin^2 {\omega t} = \dfrac{1}{2} - \dfrac{1}{2} \cos{2\omega t}$

This tells us $\sin^2{\omega t}$ looks like,

- a cosine at twice the frequency, $\cos{2\omega t}$,

- scaled down by half,

- flipped top-to-bottom by the minus sign,

- and DC shifted up by half so it fits between $0$ and $+1$.

The power calculation we did earlier has a scaling term $\text V_{peak}/\text R$ in front of $\sin^2$, but it is otherwise the same.

Find the average power

As an engineer I like to do things the easy way. Let’s just look at the black power curve for our example circuit and find its average value by inspection,

It is a shifted cosine. The average of any sinusoid (over a full cycle) is its centerline. A sinusoid is always centered on half its peak value. So the average power is,

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{\text V^2_{peak}}{\text R}\, \dfrac{1}{2}$

With actual circuit values,

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{2^2}{1300}\, \dfrac{1}{2} = 1.5\,\text{mW}$

The average power is $1/2$ of the peak value. The vertical scale is $1\,\text{mW}$ per division.

Alert! The eyeball-the-average method works with nice symmetric signals where it’s easy to predict the average. If the average isn’t totally obvious go ahead and do the calculus. Two non-easy examples are triangle waves and sawtooth waves.

Oh alright, let’s do the calculus

The power is $p = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\sin^2{\omega t}$

or equivalently using the half-angle identity,

$p = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\left (\dfrac{1}{2} - \dfrac{1}{2} \cos{2\omega t} \right )$

Let’s find the average power over one cycle.

The way you take the average of a continuously changing function $f(x)$ over an interval $a$ to $b$ is with this integral equation, review

$f_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{b-a}\displaystyle \int_a^b f(x) \,dx$

Fill in the equation with our power expression. If we make the limits the limits $0$ to $2\pi$ it means we take the average over one or more full cycles,

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{2\pi-0}\displaystyle \int_0^{2\pi} p(t) \,dt$

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{2\pi}\displaystyle \int_0^{2\pi} \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\,\left (\dfrac{1}{2} - \dfrac{1}{2} \cos{2\omega t} \right ) \,dt$

Factor out all the constants,

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{2\pi}\dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\dfrac{1}{2}\left (\displaystyle \int_0^{2\pi}dt - \displaystyle \int_0^{2\pi}\cos{2\omega t} \,dt \right )$

Perform the two integrals,

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{2\pi}\dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\dfrac{1}{2}\left (t \,\bigg \vert_0^{2\pi} - \dfrac{1}{2\omega}\sin{2\omega t}\,\bigg \vert_0^{2\pi} \right )$

The first evaluation, $t \,\bigg \vert_0^{2\pi} = 2\pi - 0 = 2\pi$.

The second evaluation, $\dfrac{1}{2\omega}\sin{2\omega t}\,\bigg \vert_0^{2\pi} = \dfrac{1}{2\omega}(\sin{2\omega \,2\pi} - \sin{2\omega \,0}) = 0 - 0 = 0$

The second evaluation tell you something you already know—the area under one or more full cycles of sine is $0$.

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{1}{2\pi}\dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\dfrac{1}{2}\,(2\pi)$

$p_{avg} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\dfrac{1}{2}$

Match AC power to DC power

Now it’s time to match AC power to DC power.

AC power: $p_{avg} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\text R}\dfrac{1}{2}$

DC power: $p_\text{DC} = \dfrac{\text V_\text{DC}^2}{\text R}$

How is $V_{peak}$ related to $\text V_\text{DC}$ if we want the power dissipation to be the same?

Set the two power expressions equal and see what happens.

show answer

$\dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{\cancel{\text R}}\dfrac{1}{2} = \dfrac{\text V_\text{DC}^2}{\cancel{\text R}}$

Take the square root of both sides to get back to just voltage,

$\sqrt{\dfrac{\text V_{peak}^2}{2}} = \sqrt{\text V_\text{DC}^2}$

$\dfrac{\text V_{peak}}{\sqrt 2} = \text V_\text{DC}$

If you are given $\text V_{peak}$ this tells you the DC voltage that dissipates the same power.

If you are given $\text V_\text{DC}$ and want the same power dissipation from the AC voltage pick the peak value such that,

$\text V_{peak} = \sqrt 2\,\text V_\text{DC}$

RMS voltage

This way of thinking about AC voltage is called the root mean square voltage. Where does this name come from? Look back through the steps we did,

- In the last step we took a square root.

- In statistics it is common to shorten square root to just root.

- We took the square root of the average of the power curve.

- In statistics, average means the same thing as mean.

- To get the power curve we squared the sine wave voltage.

The number that comes out is the Root of the Mean of the Square of the peak voltage, so it’s called the RMS voltage.

For voltage in the shape of a sine wave the RMS voltage is,

$\text V_\text{RMS} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}}{\sqrt 2}$

The RMS voltage of a unit sine wave. This gives you a visual impression of the proportions of a sine and its corresponding RMS value.

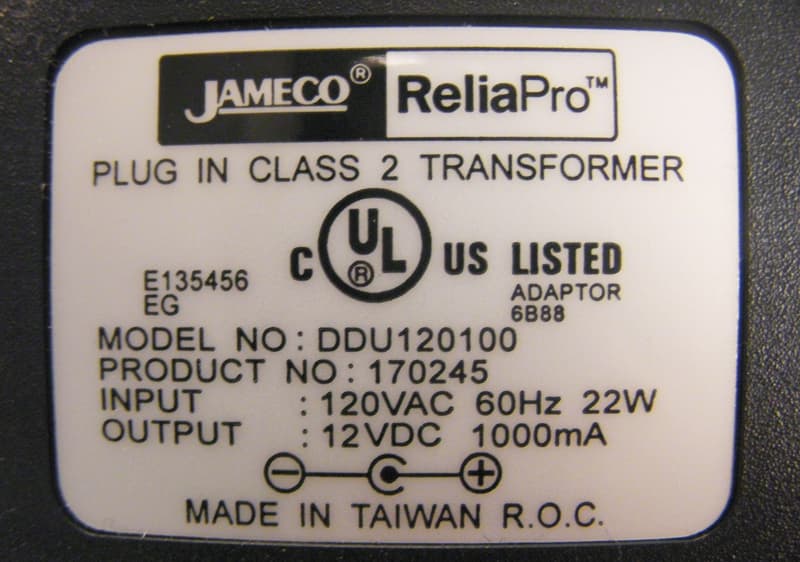

An AC voltage is almost always identified by its RMS voltage. It is rare to use peak voltage. The input voltage to this power adaptor is rated at $120\,\text{VAC}$, which is an RMS voltage value,

Concept check

In the United states the nominal wall plug voltage is $120\,\text{VAC}$. This is an RMS value, and the voltage is a sine wave.

What are the peak positive and peak negative values of $120\,\text{VAC}$?

show answer

$\text V_{peak} = \sqrt 2\,\text V_\text{DC}$

$\text V_{peak} = 1.414\cdot 120$

$\text V_{peak} = 170\,\text V$

The wall plug voltage goes as high as $+170\,\text V$ and as low as $-170\,\text V$.

In many parts of the world the nominal wall plug voltage is $230\,\text{VAC}$.

What are the peak positive and peak negative values of $230\,\text{VAC}$?

show answer

$\text V_{peak} = \sqrt 2\,\text V_\text{DC}$

$\text V_{peak} = 1.414\cdot230$

$\text V_{peak} = 325\,\text V$

The wall plug voltage goes as high as $+325\,\text V$ and as low as $-325\,\text V$.

What DC voltage dissipates the same power as a $4\,\text V$ peak sine wave?

show answer

This is the same as finding the RMS value of a $4\,\text V$ peak sine wave.

$\text V_{peak} = \sqrt 2\,\text V_\text{RMS}$

$4 = 1.414\,\text V_\text{RMS}$

$\text V_\text{RMS} = 2.83\,\text V$

Summary

The RMS voltage of a sine wave is,

$\text V_{\text{RMS}} = \dfrac{\text V_{peak}}{\sqrt 2} = 0.707\,\text V_{peak}$

$\text V_{\text{RMS}}$ does not depend on the sine wave frequency.