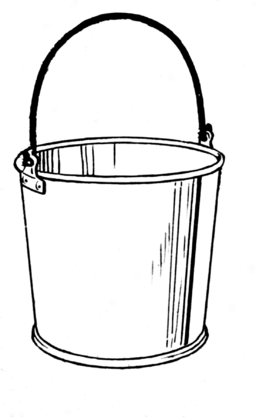

A capacitor is like a bucket

For a given $\text C$, the amount of stored charge is directly proportional to the voltage on the capacitor.

For a given $v$, a larger capacitor (higher $\text C$) stores more charge than a smaller $\text C$.

For a given amount of charge $q$, the voltage on a smaller capacitor will be high, and the voltage on a large capacitor will be small.

A capacitor is like a “bucket” for charge.

Charge flowing into a capacitor is like water pouring from a garden hose.

The amount of charge in the bucket increases as the current source “pours” more charge in. As the bucket fills, the level of water in the bucket goes up. This corresponds to the capacitor voltage going up.

The amount of water in a bucket is measured in liters or gallons. That’s equivalent to the amount of charge stored on the capacitor plates, measured in coulombs.

When the current source stops pouring, the amount of charge doesn’t change anymore. The water level (voltage) stays right where it is. It will stay that way as long as there is no path for water to leak out of the bucket (leakage is a story for another day).

The size of the bucket is indicated by its capacitance, $\text C$. Big buckets have big $\text C$, tiny buckets have tiny $\text C$, like picoFarads $(10^{-12})$ tiny.

If you add charge to the bucket it changes the water level (the voltage). Suppose the bucket is really big $($very large $\text C)$. If you pour some charge into the bucket, the water level (voltage) goes up to a certain level. If you pour that same amount of charge into a smaller bucket (smaller capacitor), it will fill up much faster and possibly overflow (exceed the capacitor’s voltage rating).

AC Circuits: In the example we worked on in this article we poured charge into a bucket but never took any out. When we study AC circuits, charge will flow both ways, in and out of the capacitor. That is why it’s called alternating current. The water level (voltage) rises and falls depending on how often the current changes direction (the frequency). One thing that capacitors can do that buckets can’t is hold a negative charge. That’s when the current flows onto the bottom plate. A negative voltage buids up. I haven’t seen a bucket do that.

Filling the bucket: If you want a wire to change voltage very fast, make sure there are no big capacitors attached. A capacitor will not change its voltage unless you provide all the charge it wants, and that takes time. (It takes a loooong time to fill a swimming pool from a garden hose.) To make a circuit go super fast, capacitors have to be super small. That’s one of the reasons we build circuits on small silicon chips. The capacitance of the super small wires is super small, and therefore super fast. Modern computer chips can run as fast as they do because of this, at frequencies of $3\,\text{GHz}$, $(3 \times 10^{9})$ or $3$ billion cycles per second.

Written by Willy McAllister.