Electric field

Coulomb’s Law describes forces acting at a distance between two charges. The idea of “force at a distance” has always puzzled scientists. It just doesn’t seem plausible.

There is an alternative explanation. We can describe the concept as two distinct steps. Rather than saying two charges push on each other with a “force at a distance,” we say,

- An electric charge fills space with an electric field.

- A nearby charge experiences a force because of the electric field at the location of the introduced charge.

Written by Willy McAllister.

Contents

- Coulomb’s Law

- Electric field defined

- Electric field near an isolated point charge

- Electric field near a dipole

- Electric field near multiple point charges

- Electric field from distributed charge

- Units of electric field

- Electric field between capacitor plates

- How I think about electric field

- Further thoughts

We introduce electric fields starting with static charges. Even though the electric field concept is not required for electrostatic problems we do this to get some practice with the concept and picturing electric fields in our head.

What is a field?

A field is a physical quantity that has a value everywhere in space. As an example, temperature is a field. Every point in space has a temperature. Since temperature is a scalar quantity (has magnitude but does not have direction) it is called a scalar field.

Wind is another type of field. At every point in the atmosphere the air is moving at some speed in some direction. That means each point in space is associated with a vector quantity. That makes wind a vector field. Gravity and magnetism are other examples of a vector field.

Coulomb’s Law

Coulomb’s Law says the force in newtons between two charges is,

$\vec F = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{q\, q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i$

$\vec F$ is the Coulomb force. This force is the essence of electricity.

$r^2$ in the denominator is the square of the distance between $q_i$ and $q$.

$\dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}$ is a constant measured by experiment, $9 \times 10^9$ newton-meter$^2/$coulomb$^2$.

$q_i$ and $q$ are the two charges pushing or pulling on each other. We give $q$ a special role when we define the electric field.

The force acts along the line between the two charges, as indicated by the $\hat{r_i}$ symbol (pronounced “r-hat”). $\hat{r_i}$ is a vector with magnitude $1$ that points from $q$ to $q_i$. It tells you which way the force vector points.

Do not get hung up on which way $\hat r_i$ points, toward $q$ or toward $q_i$. It is so easy to mess up this vector notation that we always figure out direction in our head, separate from the calculation of magnitude.

Electric field defined

To find the force on $q$ you need to know three things: the value of $q$, the value of $q_i$, and the distance between them. Suppose, just for convenience, we assume $q = 1$. Then we would just have to know two things to find the force: $q_i$ and the distance. This is how electric field is defined. One charge is assigned to be a “test charge” with a value $q = 1$. The electric field tells you the force on the test charge caused by the other charge, $q_i$.

If $q$ happens to be $1$, the electric field tells you the force on $q$. If $q$ is a different value, find the force by multiplying the electric field by $q$,

$\vec F = q \,\vec E$

Another way to say the same thing is the electric field is the “normalized” electric force, or the force per coulomb,

$\vec E = \dfrac{\vec F}{q}$

From this equation you can see the dimensions of electric field are newtons/coulomb. This definition of electric field works for any number of charges $q_i$, in any arrangement.

Electric field near an isolated point charge

Find the field created by a point charge.

Start with the definition of electric field and replace $\vec F$ with Coulomb’s Law,

$\vec E = \dfrac{\vec F}{q} = \dfrac{1}{q} \,\dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{q\, q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i$

The $\dfrac{1}{q}$ term cancels the $q$ in the numerator of Coulomb’s Law,

$\vec E = \dfrac{1}{\cancel q} \,\dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{\cancel q\, q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i$

Leaving behind the source charge $q_i$,

$\vec E = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i$

There is just one charge mentioned in the definition of electric field.

Concept check

What is the magnitude of the electric field $1\,\text{cm}$ away from a $5\,\text{pC}$ point charge?

show answer

It is a good idea to manage the magnitude and direction separately.

$|\vec E| = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{q_i}{r^2}$

$|\vec E| = 9 \times 10^9\cdot\dfrac{5\times 10^{-12}}{0.01^2}$

$|\vec E |= 450\,\text N/\text m$

$1\,\text{cm}$ away from a $5\,\text{pC}$ charge the electric field strength is $450\,\text N/\text m$.

If you put a $1\,\text C$ charge at that location it would be repelled with a force of $450$ newtons.

If you put a $1\,\text{pC}$ charge at that location it be repelled with a force of,

$|\vec F| = q\,|\vec E|$

$|\vec F| = 1\,\text{pC} \cdot 450\,\text N/\text C = 450\,\text{pN}$

Which way does the electric field vector point?

show answer

The electric field vector $\vec E$ points in the same direction as $\hat r$, a straight line between the $5\,\text{pC}$ charge and the location you pick.

Since both the $5\,\text{pC}$ charge and the imagined $1\,\text C$ test charge are positive, they repel. So the electric field vector points in the same direction as the force vector, away from the positive charge.

Visualize the electric field near a point charge

The electric field around a single isolated point charge, $q_i$, is given by,

$\vec E = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{\text q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i$

The electric field vectors point straight away from an isolated positive point charge in all directions, as shown on the left. If the point charge is negative then $q_i$ brings a minus sign to the equation and the field vector points straight at an isolated negative charge.

The magnitude of the electric field falls off as $1/r^2$ as you move away from either point charge. Notice the arrows farther away from the point charge are drawn shorter.

Electric field near a dipole

Two charges with opposite signs near each other is called a dipole (two poles). The electric field near a dipole can be visualized like this,

[source]

In a diagram like this the electric field arrows run together into continuous lines of force. The direction of the force is clear, but you have to imagine the magnitude (the length of the arrows) getting shorter as you move away from the source of the field.

In your imagination, hold a small positive test charge on the end of a stick in various places around the dipole. Feel in your hand how the test charge is pushed and pulled by the two dipole charges. The force you feel should point in the direction of the arrows.

If you center the test charge directly between the dipole charges, which way does the electric field point?

Electric field near multiple point charges

If there are multiple point charges scattered about, the electric field is the vector sum of the fields from each individual $q_i$,

$\displaystyle \vec E = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\sum_i\dfrac{\text q_i}{r_i^2} \,\hat{r}_i$

You solve multiple-charge electric field problems just like electric force problems with multiple charges.

Electric field from distributed charge

If charge is spread out in a continuous distribution like a line or sphere or plane, the summation turns into an integral,

$\displaystyle \vec E = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\int\dfrac{dq}{r^2} \,\hat r$

We will find the electric field of distributed charge in upcoming articles.

Units of electric field

The units of electric field are newtons per coulomb, $\text N/\text C$.

There is a second way to specify the units, as volts per meter, $\text V/\text m$.

These two units don’t look alike, so let’s do a quick derivation. First, let’s remind ourselves of some definitions of the joule.

$1\,\text{joule (J)} = 1\,\text{newton meter}\,(\text N⋅\text m)$. $1\,\text{joule}$ is the work done on (the energy transferred to) an object when a force of $1\,\text{newton}$ pushes the object a distance of $1\,\text{meter}$.

$1\,\text{joule (J)} = 1\,\text{coulomb volt}\,(\text C⋅\text V)$. $1\,\text{joule}$ is the work done to push an electric charge of $1\,\text{coulomb}\,(\text C)$ through an electrical potential difference of $1\,\text{volt}\,(\text V)$. (This is actually the definition of the volt.)

Let’s use dimensional analysis to show $\text V/\text m$ is the same as $\text N/\text C$,

$\text{volt} = \dfrac{\text{joule}}{\text{coulomb}},\quad\text V = \dfrac{\text J}{\text C}$

Divide both sides by meters,

$\dfrac{\text{volt}}{\text{meter}} = \dfrac{\text{joule}}{\text{coulomb}}\dfrac{1}{\text{meter}},\quad\dfrac{\text V}{\text m} = \dfrac{\text J}{\text C}\cdot \dfrac{1}{\text m}$

The joule is the honorary name for a newton⋅meter,

$\dfrac{\text V}{\text m} = \dfrac{\text N⋅\text m}{\text C}\cdot \dfrac{1}{\text m}$

The meters on the right side cancel,

$\dfrac{\text V}{\text m} = \dfrac{\text N⋅\cancel{\text m}}{\text C}\cdot \dfrac{1}{\cancel{\text m}}$

$\dfrac{\text V}{\text m} = \dfrac{\text N}{\text C}\quad \checkmark$

These two forms are equivalent. There’s no scale factor to convert from $\text N / \text C$ to $\text V/\text m$.

$450 \,\text N /\text C = 450\, \text V/\text m$

Electric field between capacitor plates

When dealing with electronic circuits it is more common to see $\text V/\text m$ more often when electric field is discussed. That’s because we are more likely to know voltage and the size of the circuit rather than force and an amount of charge.

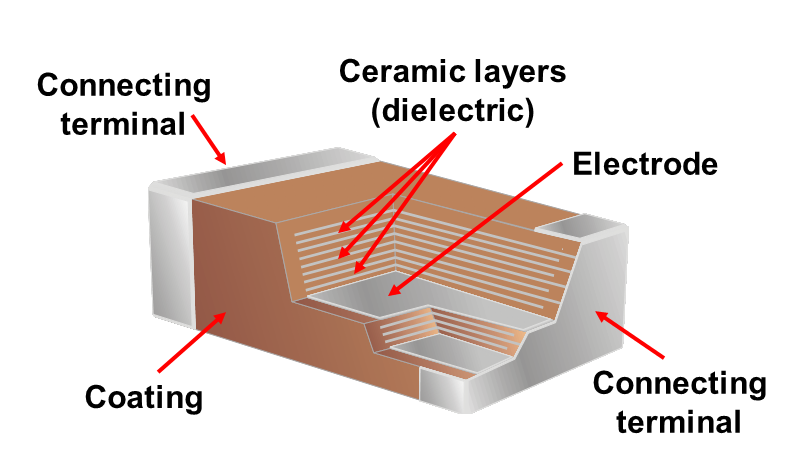

Let’s take a moment to talk about the electric field between two capacitor plates. I’m jumping over some important theory, but I want to share how the $\text V/\text m$ units work in real life.

In an upcoming article, electric field near a plane of charge, we learn the electric field near a wide flat plate is constant, independent of the distance away from the plate. Two wide flat plates placed close together but not touching is called a capacitor. The electric field between two capacitor plates looks like this, (This is the field near the center of the plates. Don’t worry about the edges for now.)

The field arrows point straight down from the positive plate toward the negative plate. All arrows are the same length. We learned above that electric field can be measured with units of $\text V/\text m$.

If the voltage on the capacitor is $5\,\text V$ and $d = 0.1\,\text{mm}$, what is the magnitude of the electric field?

show answer

Electric field can be measured with units of $\text V/\text m$, and we’ve been given values for both.

$v = 5\,\text V$

$d = 0.0001\,\text m$

$|\vec E| = \dfrac{5\,\text V}{0.0001\,\text m}$

$|\vec E| = 50{,}000\,\text V/\text m$

That may seem like an astonishingly large number for an electric field, but it is not an unusual value at all. The voltage and dimension in this example are reasonable values for a typical surface mount capacitor. The common 1608 surface mount capacitor has overall dimensions $1.6 \,\text{mm} \times 0.8\,\text{mm} \times 0.9\,\text{mm}$.

what happens near the edges?

The theory about straight constant lines of electric field holds for infinite plates. The theory works really well when the plates are finite but very large compared to the distance separating them, as long as you stay away from the edges. This is a good description of capacitor plates.

What happens to the electric field near the edges of a capacitor plate? The electric field lines bulge out to the side slightly. They extend a short ways out into the free space outside the plates.

The farther you get away from the plates the weaker the electric field gets (shorter arrows). The vast majority of the electric field exists between the plates.

How I think about electric field

I imagine a small positive test charge glued to the end of an imaginary stick. (Be sure your imaginary stick doesn’t conduct. Make it out of wood or plastic). Explore the electric field by holding the test charge in different places in the field. The test charge is pushed or pulled by other charges in the neighborhood. The force you feel on the test charge (magnitude and direction) divided by the value of the small test charge on the end of the stick is the electric field vector at that point. Even if you take away the test charge, the electric field is still there.

Why is the test charge positive?

The convention for measuring electric field is to use a positive $+q$ test charge. It resembles a proton. If you like, you may attach an electron on the end of the stick. If your negative test charge is pushed in the opposite direction of the electric field vector.

Summary

The equation for electric field is similar to Coulomb’s Law. We assign one of the $q$’s in the numerator of Coulomb’s Law to play the role of test charge. The other charge(s) in the numerator, $q_i$, create the electric field we want to study.

$\text{Coulomb’s Law: }\qquad\vec F = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\dfrac{q\, q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i \qquad\text{newtons}$

$\text{Electric field: }\,\,\,\,\vec E = \dfrac{\vec F}{q} = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\,\,\,\,\dfrac{q_i}{r^2}\,\hat r_i \qquad\text{newtons/coulomb}$

Where $\hat r_i$ are unit vectors indicating the line between each $q_i$ and $q$.

The value of the electric field at a point only depends on the value of the source charge creating the field, not on the value of the test charge.

Here is the mind-blowing step: Once we describe the electric field, we don’t need $q$ any more! We can forget about $q$ and the electric field is still there. Without $q$, the electric field is described as a property of the space surrounding the other charge(s), $q_i$.

This may sound like a reasonable idea to you, or it may sound like complete nonsense. Both reactions are equally valid. The main justification for the theory is it produces spectacular theoretical and real-world results.

Further thoughts

We defined electric field. There isn’t any new physics. We just rearranged the electric force computation.

If the idea of force “at a distance” implied by Coulomb’s Law seems troublesome, you are in a big club. Perhaps having the force come from an electric field eases your discomfort. On the other hand, you might reasonably ask if an electric field is any more “real”. Whether an electric field is real or not is a topic for philosophers and physicists. Real or not, the notion of an electric field is really useful tool for predicting what happens to charge.

When charges are static (not moving, or not moving very fast) the electric field point of view gives exactly the same answer as Coulomb’s Law. So why do we need the electric field? We study electric fields because the theory blossoms in two important cases.

-

When charges move (current) there is a slight delay before you can detect the movement some distance away. Coulomb’s Law does not predict a delay, but there certainly is one. The observed delay can be described as a disturbance in the electric field. The disturbance propagates through a wire or the air at the speed of light, much like ripples propagate across the surface of a pond.

-

An electric field coupled with a magnetic field carries energy, and it travels through space all by itself. We call this light, an electromagnetic wave. Electric field theory explains how starlight travels through vast distances of empty space to reach our eyes.

These are advanced topics not covered here.

References

Kip, A. H. (1969), Fundamentals of Electricity and Magnetism (2nd edition, McGraw-Hill)